Журнал «Медицина неотложных состояний» Том 20, №1, 2024

Вернуться к номеру

Ендокринна дисфункція в патогенезі бойової хірургічної травми й посттравматичного стресового розладу (науковий огляд)

Авторы: Усенко О.Ю. (1), Хоменко І.П. (2), Коваленко А.Є. (3), Негодуйко В.В. (4), Місюра К.В. (5), Забронський А.В. (2)

(1) - Національний науковий центр хірургії та трансплантології ім. О.О. Шалімова НАМН України, м. Київ, Україна

(2) - Київська міська клінічна лікарня № 8, м. Київ, Україна

(3) - Національний університет охорони здоров’я України ім. П.Л. Шупика, м. Київ, Україна

(4) - Військово-медичний клінічний центр Північного регіону, м. Харків, Україна

(5) - ДУ «Інститут проблем ендокринної патології ім. В.Я. Данилевського НАМН України», м. Харків, Україна

Рубрики: Медицина неотложных состояний

Разделы: Справочник специалиста

Версия для печати

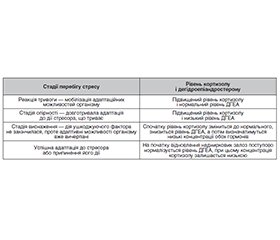

Сучасні воєнні дії створили унікальні проблеми для медичної, хірургічної та реабілітаційної допомоги військовозобов’язаним, які отримали поранення в бойових умовах. Досвід надання медичної допомоги учасникам бойових дій показав, що дисфункція ендокринної системи є провідною патогенетичною ланкою, яка впливає на організм людини при бойовій хірургічній травмі та посттравматичних стресових розладах. Основний патогенетичний механізм травми й посттравматичних стресових розладів пов’язаний з дисфункцією гіпоталамо-гіпофізарно-надниркової осі. У нейроендокринних механізмах розвитку стресу беруть участь гормони: кортизол, дегідроепіандростерон, адреналін, норадреналін, які регулюють і контролюють реакцію на стрес, а також відображають стадійність його перебігу й адаптивні можливості організму. Дисфункція гіпоталамо-гіпофізарно-тиреоїдної осі має велике значення в регуляції як гострого, так і хронічного стресу з клінічним розвитком різних захворювань щитоподібної залози: гіпертиреозу, хвороби Грейвса, автоімунних тиреопатій, зобної трансформації. У зв’язку з цим має практичне значення дослідження в клініці основних показників гіпофізарно-надниркової і гіпофізарно-тиреоїдної функції, моніторинг функції надниркових залоз і щитоподібної залози. Корекція цих порушень, лікування і реабілітація пацієнтів з бойовими травматичними пошкодженнями повинні здійснюватися з урахуванням спеціалізованої ендокринологічної допомоги, що буде актуальним для військової медицини України в наступні роки.

The modern hostilities have created the unique challenges for medical, surgical and rehabilitation assistance to people liable for military service who have sustained injuries in the battle conditions. The experience of providing medical care for participants of modern military operations has shown that endocrine dysfunction is a leading pathogenetic link that affects the human body in combat surgical trauma and post-traumatic stress disorders. The main pathogenetic mechanism of trauma and post-traumatic stress disorders is associated with dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Hormones such as cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone, adrenaline and noradrenaline are involved in the neuroendocrine mechanisms of stress development. These hormones regulate and control the stress response, reflecting the stages of its course and the adaptive capacities of the organism. Dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis has a significant importance in the regulation of both acute and chronic stress accompanied by the clinical development of various thyroid disorders such as hyperthyroidism, Graves’ disease, autoimmune thyroidopathies and nodular transformation. Therefore, the practical significance lies in the clinical studying the key indicators of pituitary-adrenal and pituitary-thyroid function, monitoring the function of the adrenal glands and the thyroid. Correction of these disorders, the treatment and rehabilitation of patients with combat-related traumatic injuries should be carried out with specialized endocrinological assistance. This approach will be relevant for military medicine in Ukraine in the following years.

бойова хірургічна травма; посттравматичний стресовий розлад; ендокринна дисфункція

combat-related surgical injures; post-traumatic stress disorder; endocrine dysfunction

Для ознакомления с полным содержанием статьи необходимо оформить подписку на журнал.

- Usenko O.Yu., Lurin I.A., Gumenuk K.V., Nehoduiko V.V., Mykhaylusov R.M., Saliutin R.V. Оrgan-preserving operations in the abdominal gun-shot penetrating woundings of large bowel. Experience of the medical help delivery in military environment Аntiterroristic operation. The Joint Forces Operation. DOI: 10.26779/2522-1396.2021.11-12.03 (In Ukrainian).

- Usenko O.Yu., Lurin І.A., Gumenuk K.V., Nehoduiko V.V., Mikhaylusov P.M., Ryzhenko A.P., Saliutin R.V. Application of surgical magnet instruments for diagnosis and pulling out of ferromagnetic foreign bodies of abdominal cavity in the battle gun-shot trauma. The Ukrainian Journal of Clinical Surgery. 2022, July/August. 89(7–8). 30-34. DOI: 10.26779/2522-1396.2022.7-8.30 (In Ukrainian).

- Usenko O.Yu., Sydiuk A.V., Sydiuk O.E., Klimas A.S., Savenko G.Yu., Teslia O.T. The battle trauma of the esophagus. The Ukrainian Journal of Clinical Surgery. 2022, July/August. 89(7–8). 3-8. DOI: 10.26779/2522-1396.2022.7-8.03 (In Ukrainian).

- Khomenko I.P., Lurin I.A., Korol S.O., Shapovalov V.Yu., Matviichuk B.V. Conceptual principles of the wounded combatants’ evacuation, suffering military surgical trauma on the medical support levels. The Ukrainian Journal of Clinical Surgery. 2020, May/June. 87(5–6). 60-64. DOI: 10.26779/2522-1396.2020.5-6.60 (In Ukrainian).

- Khomenko І.P., Коrol S.О., Маtviychuk B.V., Ustinova L.А. Pathophysiological substantiation of medical evacuation of the wounded persons, suffering injuries of the extremities on the levels of medical support. The Ukrainian Journal of Clinical Surgery. 2019 June. 86(6). 25-29. DOI: 10.26779/2522-1396.2019.06.25 (In Ukrainian).

- Epstein A., Lim R., Johannigman J., Fox C.J., Inaba K., Vercruysse G.A. et al. Putting Medical Boots on the Ground: Lessons from the War in Ukraine and Applications for Future Conflict with Near-Peer Adversaries. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2023 Aug 1. 237(2). 364-373. doi: 10.1097/XCS.0000000000000707. Epub 2023 Apr 24.

- Fitzpatrick K.F., Pasquina P.F. Overview of the rehabilitation of the combat casualty. Mil. Med. 2010 Jul. 175 (7 Suppl). 13-7. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-10-00159.

- Karatzias T., Shevlin M., Ben-Ezra M., McElroy E., Redican E., Vang M.L., Cloitre M., Ho G.W.K., Lorberg B., Martsenkovskyi D., Hyland P. War exposure, posttraumatic stress disorder, and complex posttraumatic stress disorder among parents living in Ukraine during the Russian war. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2023 Mar. 147(3). 276-285. doi: 10.1111/acps.13529. Epub 2023 Jan 10.

- Levin Y., Ben-Ezra M., Hamama-Raz Y., Maercker A., Goodwin R., Leshem E., Bachem R. The Ukraine-Russia war: A symptoms network of complex posttraumatic stress disorder during continuous traumatic stress. Psychol. Trauma. 2023 Aug 10. doi: 10.1037/tra0001522.

- Fel S., Jurek K., Lenart-Kłoś K. Relationship between Socio-Demographic Factors and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Cross Sectional Study among Civilian Participants’ Hostilities in Ukraine. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022 Feb 26. 19(5). 2720. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19052720.

- Johnson R.J., Antonaccio O., Botchkovar E., Hobfoll S.E. War trauma and PTSD in Ukraine’s civilian population: comparing urban-dwelling to internally displaced persons. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022 Sep. 57(9). 1807-1816. doi: 10.1007/s00127-021-02176-9. Epub 2021 Oct 1.

- Ben-Ezra M., Goodwin R., Leshem E., Hamama-Raz Y. PTSD symptoms among civilians being displaced inside and outside the Ukraine during the 2022 Russian invasion. Psychiatry Res. 2023 Feb. 320. 115011. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2022.115011. Epub 2022 Dec 17.

- Boscarino J.A. Posttraumatic stress disorder and physical illness: results from clinical and epidemiologic studies. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004 Dec. 1032. 141-53. doi: 10.1196/annals.1314.011.

- Ranabir S., Reetu K. Stress and hormones. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011 Jan. 15(1). 18-22. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.77573.

- Yehuda R., Giller E.L., Southwick S.M., Lowy M.T., Mason J.W. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal dysfunction in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 1991 Nov 15. 30(10). 1031-48. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(91)90123-4.

- Persike D.S., Al-Kass S.Y. Challenges of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in Iraq: biochemical network and methodologies. A brief review. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 2020 Nov 6. 41(4). doi: 10.1515/hmbci-2020-0037.

- Tsigos C., Chrousos G.P. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, neuroendocrine factors and stress. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002 Oct. 53(4). 865-71. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00429-4.

- Raise-Abdullahi P., Meamar M., Vafaei A.A., Alizadeh M., Dadkhah M., Shafia S., Ghalandari-Shamami M., Naderian R., Samaei S.A., Rashidy-Pour A. Hypothalamus and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Review. Brain Sci. 2023 Jun 29. 13(7). 1010. doi: 10.3390/brainsci13071010.

- Pan X., Kaminga A.C., Wen S.W., Wang Z., Wu X., Liu A. The 24-hour urinary cortisol in post-traumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020 Jan 9. 15(1). e0227560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227560. eCollection 2020.

- Jones T., Moller M.D. Implications of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis functioning in posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2011 Nov-Dec. 17(6). 393-403. doi: 10.1177/1078390311420564.

- Yehuda R., Brand S.R., Golier J.A., Yang R.-K. Clinical correlates of DHEA associated with post-traumatic stress disorder. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2006 Sep. 114(3). 187-93. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00801.x.

- Pan X., Wang Z., Wu X., Wen S.W., Liu A. Salivary cortisol in post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2018 Oct 5. 18(1). 324. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1910-9.

- Josephs R.A., Cobb A.R., Lancaster C.L., Lee H.-J., Telch M.J. Dual-hormone stress reactivity predicts downstream war-zone stress-evoked PTSD. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017 Apr. 78. 76-84. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.01.013. Epub 2017 Jan 19.

- Metzger L.J., Carson M.A., Lasko N.B., Paulus L.A., Orr S.P., Pitman R.K., Yehuda R. Basal and suppressed salivary cortisol in female Vietnam nurse veterans with and without PTSD. Psychiatry Res. 2008 Dec 15. 161(3). 330-5. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.04.020. Epub 2008 Oct 25.

- Zarković M., Stefanova E., Cirić J., Penezić Z., Kostić V., Sumarac-Dumanović M., Macut D., Ivović M.S., Gligorović P.V. Prolonged psychological stress suppresses cortisol secretion. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf). 2003 Dec. 59(6). 811-6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01925.x.

- Kocijan-Hercigonja D., Sabioncello A., Rijavec M., Folnegović-Smalc V., Matijević L., Dunevski I., Tomasić J., Rabatić S., Dekaris D. Psychological condition hormone levels in war trauma. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1996 Sep-Oct. 30(5). 391-9. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(96)00011-8.

- Cleare A.J., Miell J., Heap E., Sookdeo S., Young L., Malhi G.S., O’Keane V. Hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction in chronic fatigue syndrome, and the effects of low-dose hydrocortisone therapy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001 Aug. 86(8). 3545-54. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.8.7735.

- Bolton M.J., Chapman B.P., Marwijk H.V. Low-dose naltrexone as a treatment for chronic fatigue syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2020 Jan 6. 13(1). e232502. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-232502.

- Cobb A.R., Josephs R.A., Lancaster C.L., Lee H.-J., Telch M.J. Cortisol, Testosterone, and Prospective Risk for War-zone Stress-Evoked Depression. Mil. Med. 2018 Nov 1. 183 (11-12). e535-e545. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usy065.

- Newport D.J., Nemeroff C.B. Neurobiology of posttraumatic stress disorder. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2000 Apr. 10(2). 211-8. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00080-5.

- Pan X., Kaminga A.C., Wen S.W., Liu A. Catecholamines in Post-traumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018 Dec 4. 11. 450. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00450. eCollection 2018.

- McFall M.E., Veith R.C., Murburg M.M. Basal sympathoadrenal function in posttraumatic distress disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 1992 May 15. 31(10). 1050-6. doi: 10.1016/00063223(92)90097-j.

- Stahlman S., Oh G.T. Thyroid disorders, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2008–2017. MSMR. 2018 Dec. 25(12). 2-9.

- Wang S. Traumatic stress and thyroid function. Child Abuse Negl. 2006 Jun. 30(6). 585-8. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.11.012. Epub 2006 Jun 19.

- Wells J.E., Williams T.H., Macleod A.D., Carroll G.J. Posttraumatic stress disorder: do electrical startle responses and thyroid function usefully supplement self-report? A study of Vietnam War veterans. Aust. NZJ Psychiatry. 2003 Jun. 37(3). 334-9. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01185.x.

- Toloza F.J.K., Mao Y., Menon L.P., George G., Borikar M., Erwin P.J., Owen R.R., Maraka S. Association of Thyroid Function with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Endocr. Pract. 2020 Oct. 26(10). 1173-1185. doi: 10.4158/EP-2020-0104.

- Karlović D., Marusić S., Martinac M. Increase of serum triiodothyronine concentration in soldiers with combat-related chronic post-traumatic stress disorder with or without alcohol dependence. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2004 Jun 30. 116 (11-12). 385-90. doi: 10.1007/BF03040918.

- Mason J., Southwick S., Yehuda R., Wang S., Riney S., Bremner D. et al. Elevation of serum free triiodothyronine, total triiodothyronine, thyroxine-binding globulin, and total thyroxine levels in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1994 Aug. 51(8). 629-41. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950080041006.

- Mason J., Southwick S., Johnson D., Lubin H., Charney D. Relationships between thyroid hormones and symptoms in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychosom. Med. 1995 Jul-Aug. 57(4). 398-402. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199507000-00012.

- Wang S., Mason J. Elevations of serum T3 levels and their association with symptoms in World War II veterans with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: replication of findings in Vietnam combat veterans. Psychosom. Med. 1999 Mar-Apr. 61(2). 131-8. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199903000-00001.

- Jung S.J., Kang J.H., Roberts A.L., Nishimi K., Chen Q., Sumner J.A., Kubzansky L., Koenen K.C. Posttraumatic stress disorder and incidence of thyroid dysfunction in women. Psychol. Med. 2019 Nov. 49(15). 2551-2560. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718003495. Epub 2018 Nov 29.

- Hsieh C.-T., Yen T.-L., Chen Y.-H., Jan J.-S., Teng R.-D., Yang C.-H., Sun J.-M. Aging-Associated Thyroid Dysfunction Contributes to Oxidative Stress and Worsened Functional Outcomes Following Traumatic Brain Injury. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023 Jan 17. 12(2). 217. doi: 10.3390/antiox12020217.

- Bookwalter D.B., Roenfeldt K.A., LeardMann C.A., Kong S.Y., Riddle M.S., Rull R.P. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of selected autoimmune diseases among US military personnel. BMC Psychiatry. 2020 Jan 15. 20(1). 23. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-2432-9.

- O’Donovan A., Cohen B.E., Seal K.H., Bertenthal D., Margaretten M., Nishimi K., Neylan T.C. Elevated risk for autoimmune disorders in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2015 Feb 15. 77(4). 365-74. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.06.015. Epub 2014 Jun 28.

- Kyriacou A., Tziaferi V., Toumba M. Stress, Thyroid Dysregulation, and Thyroid Cancer in Children and Adolescents: Proposed Impending Mechanisms. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2023. 96(1). 44-53. doi: 10.1159/000524477. Epub 2022 Apr 6.

- Rohleder N., Joksimovic L., Wolf J.M., Kirschbaum C. Hypocortisolism and increased glucocorticoid sensitivity of pro-Inflammatory cytokine production in Bosnian war refugees with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2004 Apr 1. 55(7). 745-51. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.11.018.

- Rohleder N., Karl A. Role of endocrine and inflammatory alterations in comorbid somatic diseases of post-traumatic stress disorder. Minerva Endocrinol. 2006 Dec. 31(4). 273-88.

- Spitzer C., Barnow S., Völzke H., John U., Freyberger H.J., Grabe H.J. Trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and physical illness: findings from the general population. Psychosom. Med. 2009 Nov. 71(9). 1012-7. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181bc76b5. Epub 2009 Oct 15.

- Mesquita J., Varela A., Medina J.L. Trauma and the endocrine system. Endocrinol. Nutr. 2010 Dec. 57(10). 492-9. doi: 10.1016/j.endonu.2010.06.012. Epub 2010 Sep 17.

- Yehuda R. Biology of posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2001. 62 Suppl 17. 41-6.

- Sabioncello A., Kocijan-Hercigonja D., Rabatić S., Tomasić J., Jeren T., Matijević L., Rijavec M., Dekaris D. Immune, endocrine, and psychological responses in civilians displaced by war. Psychosom. Med. 2000 Jul-Aug. 62(4). 502-8. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200007000-00008.

- Ismail K., Kent K., Sherwood R., Hull L., Seed P., David A.S., Wessely S. Chronic fatigue syndrome and related disorders in UK veterans of the Gulf War 1990–1991: results from a two-phase cohort study. Psychol. Med. 2008 Jul. 38(7). 953-61. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001560. Epub 2007 Sep 25.

- Miller G.E., Chen E., Zhou E.S. If it goes up, must it come down? Chronic stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in humans. Psychol. Bull. 2007 Jan. 133(1). 25-45. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.25.

- Speer K.E., Semple S., Naumovski N., D’Cunha N.M., McKune A.J. HPA axis function and diurnal cortisol in post-trauma-tic stress disorder: A systematic review. Neurobiol. Stress. 2019 Jun 4. 11. 100180. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2019.100180. eCollection 2019 Nov.

- Dajani R., Hadfield K., van Uum S., Greff M., Panter-Brick C. Hair cortisol concentrations in war-affected adolescents: A prospective intervention trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018 Mar. 89. 138-146. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.12.012. Epub 2017 Dec 26.

- Sivik T., Delimar D., Korenjak P., Delimar N. The role of blood pressure, cortisol, and prolactin among soldiers injured in the 1991-1993 war in Croatia. Integr. Physiol. Behav. Sci. 1997 Oct-Dec. 32(4). 364-72. doi: 10.1007/BF02688632.

- Smeeth D., McEwen F.S., Popham C.M., Karam E.G., Fayyad J., Saab D. et al. War exposure, post-traumatic stress symptoms and hair cortisol concentrations in Syrian refugee children. Mol. Psychiatry. 2023 Feb. 28(2). 647-656. doi: 10.1038/s41380-022-01859-2. Epub 2022 Nov 16.

- Roglić G., Pibernik-Okanović M., Prasek M., Metelko Z. Effect of war-induced prolonged stress on cortisol of persons with type II diabetes mellitus. Behav. Med. 1993 Summer. 19(2). 53-9. doi: 10.1080/08964289.1993.9937565.

- Bains M., Shortall C., Manzuangani T., Katona C., Russell I. Identifying post-traumatic stress disorder in forced migrants. BMJ. 2018 May 10. 361. k1608. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k1608.

- Vacchiano C.A., Wofford K.A., Titch J.F. Chapter 1 posttraumatic stress disorder: a view from the operating theater. Annu. Rev. Nurs. Res. 2014. 32. 1-23. doi: 10.1891/0739-6686.32.1.

- Engel C.C., Jaffer A., Adkins J., Riddle J.R., Gibson R. Can we prevent a second ‘Gulf War syndrome’? Population-based healthcare for chronic idiopathic pain and fatigue after war. Adv. Psychosom. Med. 2004. 25. 102-22. doi: 10.1159/000079061.