Международный эндокринологический журнал Том 16, №5, 2020

Вернуться к номеру

Normotensive incidental pheochromocytoma: report of a rare case with a brief review of literature

Авторы: Sen S., Bhattacharjee S., Ghosh I., Thakkar D.B., Hajra S., Dasgupta P.

Department of Surgical Oncology, Chittaranjan National Cancer Institute, 37, S. P. Mukherjee Road, Kolkata, 700026, India

Рубрики: Эндокринология

Разделы: Справочник специалиста

Версия для печати

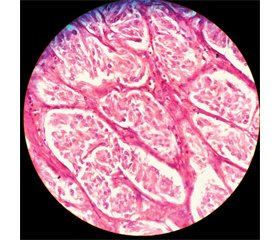

Феохромоцитома — доволі рідкісна нейроендокринна пухлина, що секретує в кровоток високоактивні адренергічні нейромедіатори — катехоламіни. При цьому не всі випадки феохромоцитом демонструють яскраву симптоматику. У клінічній практиці іноді трапляються приховані й атипові форми, нормотензивні (із нормальним артеріальним тиском) варіанти феохромоцитом. Найважливіший етап діагностики феохромоцитоми полягає у своєчасному розпізнаванні ознак, симптомів й інших проявів захворювання, які можуть вказувати на необхідність подальшого обстеження. Автори навели рідкісний випадок нормотензивної випадково виявленої великої феохромоцитоми лівої надниркової залози. 41-річний чоловік, родом із віддаленого села, без артеріальної гіпертензії і цукрового діабету, надійшов у клініку з попереднім діагнозом інциденталоми надниркових залоз. За даними ультразвукового обстеження черевної порожнини, у пацієнта запідозрено утворення лівої надниркової залози розміром 47 × 36 мм. За винятком скарг на невиражений біль у верхній частині живота, пацієнт не вказував на біль голови, приступи серцебиття, надмірне потовиділення або зміну маси тіла. Сімейний анамнез стосовно нейрофіброматозу або будь-яких пухлин щитоподібної залози, прищитоподібної залози, нирок та інших органів черевної порожнини не обтяжений. Пацієнт правильної будови тіла, у задовільному стану, без кушингоїдних симптомів й уражень шкірних покривів. У лежачому і в стоячому положеннях протягом двох хвилин його частота серцевих скорочень та артеріальний тиск (АТ) становили 76 уд/хв і 132/80 мм рт.ст., 90 уд/хв і 126/76 мм рт.ст. відповідно. Не відзначалося жодних офтальмологічних порушень або змін із боку органів грудної клітки й органів черевної порожнини. Інтенсивний моніторинг АТ не виявив піків пароксизмальної гіпертензії. За відсутності артеріальної гіпертензії та інших класичних клінічних особливостей феохромоцитоми в поєднанні з нормальним рівнем метанефрину в плазмі для авторів було несподіванкою, що утворення при гістологічному дослідженні виявився феохромоцитомою. Лише тимчасове підвищення АТ під час операції видалення пухлини вказувало на можливість феохромоцитоми.

Феохромоцитома — довольно редкая нейроэндокринная опухоль, которая секретирует в кровоток высокоактивные адренергические нейромедиаторы — катехоламины. При этом не все случаи феохромоцитом демонстрируют яркую симптоматику. В клинической практике иногда случаются скрытые и атипичные формы, нормотензивная (с нормальным артериальным давлением) варианты феохромоцитом. Важнейший этап диагностики феохромоцитомы заключается в своевременном распознавании признаков, симптомов и других проявлений заболевания, которые могут указывать на необходимость дальнейшего обследования. Авторы представили редкий случай нормотензивной случайно выявленной большой феохромоцитомы левого надпочечника. 41-летний мужчина, родом из отдаленного села, без артериальной гипертензии и сахарного диабета, поступил в клинику с предварительным диагнозом инциденталомы надпочечника. По данным ультразвукового обследования брюшной полости, у пациента заподозрили образование левого надпочечника размером 47 × 36 мм. За исключением жалоб на неопределенную боль в верхней части живота, пациент не указывал на головную боль, приступы сердцебиения, чрезмерное потоотделение или изменение массы тела. Семейный анамнез в отношении нейрофиброматоза или любых опухолей щитовидной железы, паращитовидных желез, почек и других органов брюшной полости не отягощен. Пациент правильного телосложения, в удовлетворительном состоянии, без кушингоидных симптомов и поражений кожных покровов. В лежачем и в стоячем положениях в течение двух минут его частота сердечных сокращений и артериальное давление (АД) составили 76 уд/мин и 132/80 мм рт.ст., 90 уд/мин и 126/76 мм рт.ст. соответственно. Не отмечалось никаких офтальмологических нарушений или изменений со стороны органов грудной клетки и органов брюшной полости. Интенсивный мониторинг АД не обнаружил пиков пароксизмальной гипертензии. При отсутствии артериальной гипертензии и других классических клинических особенностей феохромоцитомы в сочетании с нормальным уровнем метанефрина в плазме для авторов было неожиданностью, что образование при гистологическом исследовании оказалось феохромоцитомой. Только временное повышение АД во время операции удаления опухоли указывало на возможность феохромоцитомы.

Normotensive pheochromocytoma is a rare clinical entity that poses a pre-operative diagnostic challenge. Especially so, when the patient is clinically and biochemically silent. Initially diagnosed as incidentaloma, a biochemical panel of adrenal hormonal levels, cross sectional imaging and metabolic scan are required for pre-operative diagnosis. We present a rare case of a normotensive incidentally discovered large left adrenal pheochromocytoma unfolding to us as a histological surprise along with a brief review of the literature. 41-year-old gentleman, non-hypertensive and non-diabetic, coming from a remote village, who was admitted to our hospital with a provisional diagnosis of an adrenal incidentaloma. He had a 6-month-old abdominal ultra-sonogram report which stated a 47 × 36 mm left suprarenal region mass. Except having complaints of a vague upper abdominal pain since last 1 year he gave no history suggestive of headaches, palpitations, excessive sweating or recent changes in weight. There was no family history of neurofibromatosis or any thyroid, parathyroid, kidney or other abdominal tumors. On examination he had an average built and nutritional status, with no cushingoid features or any dermatological abnormalities. In supine position and upon standing for 2 minutes his baseline pulse rate and blood pressure (BP) were 76 beats/min and 132/80 mm Hg, and 90 beats/min and 126/76 mm Hg respectively. There were no ophthalmological abnormalities or neck lumps, abnormal chest or abnormal abdominal findings. Intensive BP monitoring did not reveal any paroxysmal hypertensive peaks. In the absence of hypertension and other classical clinical features of pheochromocytoma coupled with a normal plasma metanephrine level, it was a sort of histological surprise for us that the lesion turned out to be a pheochromocytoma. Although we did preload the patient with intravenous fluids 36 hrs prior to the surgery but intraoperatively the transient increase in blood pressure while handling the tumor hinted us towards the possibility of a pheochromocytoma.

феохромоцитома; нормотензивна феохромоцитома; інциденталома надниркової залози; «мовчазна» феохромоцитома; безсимптомна феохромоцитома

феохромоцитома; нормотензивная феохромоцитома; инциденталома надпочечников; «молчаливая» феохромоцитома; бессимптомная феохромоцитома

pheochromocytoma; normotensive incidental pheochromocytoma; adrenal incidentaloma; silent pheochromocytoma; asymptomatic pheochromocytoma

Introduction

Case report

/81_2.jpg)

/82.jpg)

Discussion

/82_2.jpg)

Conclusions

- Berends A.M.A., Buitenwerf E., de Krijger R.R. et al. Incidence of pheochromocytoma and sympathetic paraganglioma in the Netherlands: A nationwide study and systematic review. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2018. 51. Р. 68-73. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2018.01.015.

- Choi Y.M. A Brief Overview of the Epidemiology of Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma in Korea. Endocrinol. Metab. (Seoul). 2020. 35(1). Р. 95-96. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2020.35.1.95.

- Clifton-Bligh R. Diagnosis of silent pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Expert Review of Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2013. 8. 1,4757. doi: 10.1586/eem.12.76.

- Zeiger M.A., Thompson G.B., Duh Q.Y. et al. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Association of Endocrine Surgeons Medical Guidelines for the Management of Adrenal Incidentalomas: executive summary of recommendations. Endocr. Pract. 2009. 15(5). Р. 450-453. doi: 10.4158/EP.15.5.450.

- NIH state-of-the-science statement on management of the clinically inapparent adrenal mass (‘‘incidentaloma’’). NIH Consens State Sci. Statements. 2002. 19(2). Р. 1-25.

- Noshiro T., Shimizu K., Watanabe T., Akama H., Shibukawa S., Miura W. et al. Changes in clinical features and long-term prognosis in patients with pheochromocytoma. American Journal of Hypertension. 2000. 13(1). Р. 35-43. doi: 10.1016/S0895-7061(99)00139-9.

- Henrik F., Magnus K., Jan C. Initial clinical presentation and spectrum of pheochromocytoma: a study of 94 cases from a single center. Endocrine Connections. 2018. 7. Р. 186-192. doi: 10.1530/EC-17-0321.

- Riester A., Weismann D., Quinkler M., Lichtenauer U.D., Sommerey S., Halbritter R. et al. Life-threatening events in patients with pheochromocytoma. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2015. 173. Р. 757-764. doi: 10.1530/EJE-15-0483.

- Kopetschke R., Slisko M., Kilisli A., Tuschy U., Wallaschofski H., Fassnacht M. et al. Frequent incidental discovery of phaeochromocytoma: data from a German cohort of 201 phaeochromocytoma. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2009. 161. Р. 355-361. doi: 10.1530/EJE-09- 0384.

- Terzolo M., Stigliano A., Chiodini I., Loli P., Furlani L., Arnaldi G. et al. AME position statement on adrenal incidentaloma. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2011. 164. Р. 851-870. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-1147.

- Zuber S.M., Kantorovich V., Pacak K. Hypertension in pheochromocytoma: characteristics and treatment. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 2011. 40(2). Р. 295. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl. 2011.02.002.

- Vassiliadi D.A., Ntali G., Vicha E., Tsagarakis S. High prevalence of subclinical hypercortisolism in patients with bilateral adrenal incidentalomas: a challenge to management. Clinical Endocrinology. 2011. 74. Р. 438-444. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03963.x.

- Chen Y., Xiao H., Zhou X. et al. Accuracy of plasma free metanephrines in the diagnosis of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocr. Pract. 2017. 23(10). Р. 1169-1177. doi: 10.4158/EP171877.OR.

- de Jong W.H., Eisenhofer G., Post W.J., Muskiet F.A., de Vries E.G., Kema I.P. Dietary influences on plasma and urinary metanephrines: implications for diagnosis of catecholamine-producing tumors. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009. 94(8). Р. 2841-2849. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0303.

- Haissaguerre M., Courel M., Caron P. et al. Normotensive incidentally discovered pheochromocytomas display specific biochemical, cellular, and molecular characteristics. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013. 98(11). Р. 4346-4354. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1844.

- Lu Y., Li P., Gan W. et al. Clinical and Pathological Characteristics of Hypertensive and Normotensive Adrenal Pheochromocytomas. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes. 2016. 124(6). Р. 372-379. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-100911.

- Fottner C., Helisch A., Anlauf M., Rossmann H., Musholt T.J., Kreft A. et al. 6-18F-fluoro-L dihydroxyphenylalanine positron emission tomography is superior to 123I-metaiodobenzyl-guanidine scintigraphy in the detection of extraadrenal and hereditary pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas: correlation with vesicular monoamine transporter expression. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010. 95(6). Р. 2800-2810. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2352.

- Archier A., Varoquaux A., Garrigue P., Montava M., Guerin C., Gabriel S. et al. Prospective comparison of 68Ga-DOTATATE and 18F-FDOPA PET/CT in patients with various pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas with emphasis on sporadic cases. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2016. 43(7). Р. 1248-1257. doi:10.1007/s00259-015-3268-2

- Korobkin M., Brodeur F.J., Francis I.R. et al. CT time-attenuation washout curves of adrenal adenomas and nonadenomas. AJR. 1998. 170. Р. 747-752. doi: 0361-803X/98/1703-747.

- Pena C.S., Boland G.W., Hahn P.F., Lee M.J., Mueller P.R. Characterization of indeterminate lipid-poor adrenal masses: use of washout characteristics at contrast enhanced CT. Radiology. 2000. 217. Р. 798-802.

- Szolar D.H., Kammerhuber F.H. Quantitative CT evaluation of adrenal gland masses: a step forward in the differentiation between adenomas and non-adenomas. Radiology. 1997. 202. Р. 517-521.

- Tabarin A., Bardet S., Bertherat J., Dupas B., Chabre O., Ha–moir E. et al. Exploration and management of adrenal incidentalomas. French Society of Endocrinology Consensus. Annales d’Endocrinologie. 2008. 69. Р. 487-500. doi: 10.1016/j.ando.2008.09.003.

- Fassnacht M., Arlt W., Bancos I., Dralle H., Newell-Price J., Sahdev A. et al. Management of adrenal incidentalomas: European Society of Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline in collaboration with the European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2016. 175. G1-G34. doi: 10.1530/EJE-16-0467.

- Konosu-Fukaya S., Omata K., Tezuka Y. et al. Catecho–lamine-Synthesizing Enzymes in Pheochromocytoma and Extraadrenal Paraganglioma. Endocr. Pathol. 2018. 29(4). Р. 302-309. doi: 10.1007/s12022-018-9544-5.

- Bouhouch A., Hendriks J.M., Lauwers P.R., De Raeve H.R., Van Schil P.E. Asymptomatic pheochromocytoma in the posterior mediastinum. Acta Chir. Belg. 2007. 107(4). Р. 465-467. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2007.11680101.

- Rodriguez J.M., Balsalobre M., Ponce J.L. et al. Pheochromocytoma in MEN 2A syndrome. Study of 54 patients. World J. Surg. 2008. 32(11). Р. 2520-2526. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9734-2.

- Ramachandran R., Rewari V. Current perioperative management of pheochromocytomas. Indian J. Urol. 2017. 33(1). Р. 19-25. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.194781.

- Lenders J.W.M., Duh Q.Y., Eisenhofer G., Gimenez-Roqueplo A.P., Grebe S.K.G., Murad M.H. et al. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014. 99(6). Р. 1915-1942. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1498.

- Shao Y., Chen R., Shen Z.J. et al. Preoperative alpha blockade for normotensive pheochromocytoma: is it necessary? J. Hypertens. 2011. 29(12). Р. 2429-2432. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32834d24d9.

- Lafont M., Fagour C., Haissaguerre M., Darancette G., Wagner T., Corcuff J.B., Tabarin A. Per-operative Hemodynamic Instability in Normotensive Patients With Incidentally Discovered Pheochromocytomas. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015. 100(2). Р. 417-421. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2998.

- Gaujoux S., Lentschener C., Dousset B. Per-operative hemodynamic instability in normotensive patients with incidentally discovered pheochromocytomas. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015. 100(4). L31-32. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-4401.

- Ban E.J., Yap Z., Kandil E., Lee C.R., Kang S.W., Lee J. et al. Hemodynamic stability during adrenalectomy for pheochromocytoma. Medicine. 2020. 99(7). e19104. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000019104.

- Gaujoux S., Bonnet S., Lentschener C., Thillois J.M., Duboc D., Bertherat J. et al. Preoperative risk factors of hemodynamic instability during laparoscopic adrenalectomy for pheochromocytoma. Surgical Endoscopy. 2016. 30(7). Р. 2984. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4587-x.

- Ma L., Shen L., Zhang X., Huang Y. Predictors of hemodynamic instability in patients with pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2020. Р. 1-6. doi: 10.1002/jso.26079.

- Kiernan C.M., Du L., Chen X. et al. Predictors of hemodynamic instability during surgery for pheochromocytoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2014. 21(12). Р. 3865-3871. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3847-7.

- Reimondo G., Muller A., Ingargiola E., Puglisi S., Terzolo M. Is Follow-up of Adrenal Incidentalomas Always Mandatory? Endocrinol. Metab. (Seoul). 2020. 35(1). Р. 26-35. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2020.35.1.26.

- Thompson L.D. Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal gland Scaled Score (PASS) to separate benign from malignant neoplasms: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 100 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2002. 26(5). Р. 551-566. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200205000-00002.

- Strong V.E., Kennedy T., Al-Ahmadie H., Tang L., Coleman J., Fong Y. et al. Prognostic indicators of malignancy in adrenal pheochromocytomas: clinical, histopathologic, and cell cycle/apoptosis gene expression analysis. Surgery. 2008. 143(6). Р. 759-768. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.02.007.

/81.jpg)