Журнал «Здоровье ребенка» Том 17, №6, 2022

Вернуться к номеру

Фізіологічна роль та діагностичне значення антимюллерового гормона в педіатрії

Авторы: Сорокман Т.В., Хлуновська Л.Ю., Колєснік Д.І., Остапчук В.Г.

Буковинський державний медичний університет, м. Чернівці, Україна

Рубрики: Педиатрия/Неонатология

Разделы: Справочник специалиста

Версия для печати

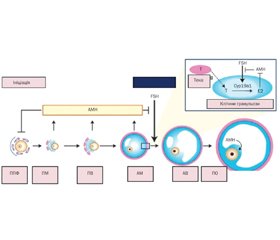

Актуальність. Антимюллерів гормон (АМГ) сьогодні набув популярності як маркер оваріального резерву. Важливим є визначення місця і ролі АМГ у дітей. Мета роботи: провести аналіз даних наукової літератури щодо ролі АМГ у педіатричній практиці. Матеріали та методи. Автори провели огляд літератури в PubMed, обмежившись статтями англійською мовою та оновленням пошуку в лютому 2022 року. Пошуковим терміном був «антимюллерів гормон». Загалом було виявлено 437 рукописів, включаючи 37 оглядових статей. Поступово звузили пошук із фільтрами клінічних досліджень та систематичних оглядів до 75 статей. Потім списки літератури оригінальних та оглядових статей були перевірені для забезпечення повноти огляду. АМГ відповідає за диференціювання гонад, провокує регресію мюллерових проток у плода чоловічої статі, корелює з каріотипом, статевим розвитком, рівнем лютеїнізуючого гормона, фолікулостимулюючого гормона (ФСГ), а його рівні в сироватці відображають резерв яєчників навіть у дитинстві. Рівень АМГ у сироватці крові високий від внутрішньоутробного періоду до статевого дозрівання. У постнатальному періоді секреція АМГ яєчками стимулюється ФСГ і сильно пригнічується андрогенами. АМГ має клінічну цінність як маркер тестикулярної тканини в чоловіків iз відмінностями в статевому розвитку та крипторхізмом, а також при оцінці персистуючого синдрому мюллерової протоки. Визначення АМГ є корисним для оцінки функції статевих залоз без необхідності проведення стимуляційних тестів й орієнтує лікаря при встановленні етіологічного діагнозу дитячого чоловічого гіпогонадизму. У жінок АМГ використовується як прогностичний маркер оваріального резерву та фертильності. Використання критеріїв, розроблених для дорослих жінок, є проблематичним для дівчат-підлітків, оскільки клінічні ознаки, пов’язані із синдромом полікістозних яєчників (СПКЯ), є нормальними явищами статевого дозрівання. АМГ може бути використаним як додатковий критерій у діагностиці СПКЯ у підлітків. Однак відсутність міжнародного стандарту для АМГ обмежує порівняння між аналізами АМГ. Висновки. АМГ має широку клінічну діагностичну корисність у педіатрії, але інтерпретація часто є складною та має здійснюватися в контексті не лише віку та статі, а й стадії розвитку та статевого дозрівання дитини. Визнання ролі АМГ за межами розвитку та дозрівання статевих залоз може започаткувати нові діагностичні та терапевтичні застосування, які ще більше розширять його використання в педіатричній практиці.

Background. Anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) has now gained popularity as a marker of ovarian reserve. It is important to determine the place and role of AMH in children. The purpose of this work was to analyze the data of the scientific literature on the role of AMH in pediatric practice. Materials and methods. A review of the literature in PubMed was conducted, limiting itself to articles in English and updating the search in February 2022. The search term was “anti-Mullerian hormone”. A total of 437 manuscripts were found, including 37 review articles. The search was gradually narrowed with filters of clinical trials and systematic reviews to 75 articles. The references of the original and review articles were then checked to ensure a complete review. AMH is responsible for the differentiation of the gonads, provokes the regression of Mullerian ducts in the male fetus, correlates with karyotype, sexual development, levels of luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and its serum levels reflect the ovarian reserve in women, even in childhood. Serum AMH is high from prenatal life to puberty. In postnatal period, the secretion of AMH by the testes is stimulated by follicle-stimulating hormone and strongly inhibited by androgens. AMH is of clinical value as a marker of testicular tissue in men with differences in sexual development and cryptorchidism, as well as in the assessment of persistent Mullerian duct syndrome. Determination of AMH is useful for assessing the function of the gonads without the need for stimulation tests and guides the etiological diagnosis of childhood male hypogonadism. In women, AMH is used as a prognostic marker of ovarian reserve and fertility. The use of criteria developed for adult women is problematic for adolescent girls, as clinical signs associated with polycystic ovary syndrome are normal phenomena of puberty. AMH can be used as an additional criterion in the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescents. However, the lack of an international standard for AMH limits comparisons between AMH analyzes. Conclusions. AMH has broad clinical diagnostic utility in pediatrics, but interpretation is often complex and should be made in the context of not only the age and sex, but also the stage of development and puberty of the child. Recognition of the role of AMH beyond the development and maturation of the gonads may lead to new diagnostic and therapeutic applications that will further expand its use in pediatric practice.

антимюллерів гормон; підлітки; огляд

anti-Mullerian hormone; adolescents; review

Фізіологія антимюллерового гормона: теоретична основа

Висновки

- Jost A. The age factor in the castration of male rabbit fetuses. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1947. 66. 302-303.

- Jost A. A new look at the mechanisms controlling sex differentiation in mammals. Johns Hopkins Med. J. 1972. 130(1). 38-53.

- Sansone A., Isidori A.M., Kliesch S., Schlatt S. Immunohistochemical characterization of the anti-Müllerian hormone receptor type 2 (AMHR-2) in human testes. Endocrine. 2020. 68(1). 215-221. doi: 10.1007/s12020-020-02210-x.

- Chemes H.E., Rey R.A., Nistal M. et al. Physiological androgen insensitivity of the fetal, neonatal, and early infantile testis is explained by the ontogeny of the androgen receptor expression in Sertoli cells. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008. 93(11). 4408-4412. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0915.

- Yates A.P., Jopling H.M., Burgoyne N.J., Hayden K., Chaloner C.M., Tetlow L. Paediatric reference intervals for plasma anti-Müllerian hormone: comparison of data from the roche elecsys assay and the beckman coulter access assay using the same cohort of samples. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2019. 56(5). 536-547. doi: 10.1177/0004563219830733.

- Bedenk J., Vrtačnik-Bokal E., Virant-Klun I. The role of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) in ovarian disease and infertility. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2020. 37(1). 89-100. doi: 10.1007/s10815-019-01622-7.

- Oh S.R., Choe S.Y., Cho Y.J. Clinical application of serum anti-Müllerian hormone in women. Clin. Exp. Reprod. Med. 2019. 46(2). 50-59. doi: 10.5653/cerm.2019.46.2.50.

- Edelsztein N.Y., Racine C., di Clemente N., Schteingart H.F., Rey R.A. Androgens downregulate anti-Müllerian hormone promoter activity in the Sertoli cell through the androgen receptor and intact steroidogenic factor 1 sites. Biol. Reprod. 2018. 99(6). 1303-1312. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioy152.

- Dumont A., Robin G., Catteau-Jonard S. et al. Role of Anti-Müllerian Hormone in pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: a review. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2015. 13. 137. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-015-0134-9.

- Dewailly D., Lujan M.E., Carmina E. et al. Definition and significance of polycystic ovarian morphology: a task force report from the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2014. 20(3). 334-52. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmt061.

- Clarke T.R., Hoshiya Y., Yi S.E., Liu X., Lyons K.M., Donahoe P.K. Müllerian inhibiting substance signaling uses a bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-like pathway mediated by ALK2 and induces SMAD6 expression. Mol. Endocrinol. 2001. 15(6). 946-959. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.6.0664.

- Cohen-Haguenauer O., Picard J.Y., Mattéi M.G. et al. Mapping of the gene for anti-Müllerian hormone to the short arm of human chromosome 19. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1987. 44(1). 2-6. doi: 10.1159/000132332.

- Mishina Y., Rey R., Finegold M.J. et al. Genetic analysis of the Müllerian-inhibiting substance signal transduction pathway in mammalian sexual differentiation. Genes. Dev. 1996. 10(20). 2577-2587. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.20.2577.

- Nachtigal M.W., Ingraham H.A. Bioactivation of Müllerian inhibiting substance during gonadal development by a kex2/subtilisin-like endoprotease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996. 93(15). 7711-7716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7711.

- Pépin D., Hoang M., Nicolaou F. et al. An albumin leader sequence coupled with a cleavage site modification enhances the yield of recombinant C-terminal Mullerian inhibiting substance. Technology. 2013. 1(1). 63-71. doi: 10.1142/S2339547813500076.

- Clarke T.R., Hoshiya Y., Yi S.E., Liu X., Lyons K.M., Donahoe P.K. Müllerian inhibiting substance signaling uses a bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-like pathway mediated by ALK2 and induces SMAD6 expression. Mol. Endocrinol. 2001. 15(6). 946-959. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.6.0664.

- Wilson C.A., di Clemente N., Ehrenfels C. et al. Mullerian inhibiting substance requires its N-terminal domain for maintenance of biological activity, a novel finding within the transforming growth factor-beta superfamily. Mol. Endocrinol. 1993. 7(2). 247-257. doi: 10.1210/mend.7.2.8469238.

- Nilsson E., Rogers N., Skinner M.K. Actions of anti-Mullerian hormone on the ovarian transcriptome to inhibit primordial to primary follicle transition. Reproduction. 2007. 134. 209-21. doi: 10.1530/REP‑07-0119.

- Xu H., Zhang M., Zhang H. et al. Clinical Applications of Serum Anti-Müllerian Hormone Measurements in Both Males and Females: An Update. Innovation (NY). 2021. 2(1). 100091. doi: 10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100091.

- Yates A.P., Jopling H.M., Burgoyne N.J., Hayden K., Chaloner C.M., Tetlow L. Paediatric reference intervals for plasma anti-Müllerian hormone: comparison of data from the Roche Elecsys assay and the Beckman Coulter Access assay using the same cohort of samples. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2019. 56(5). 536-547. doi: 10.1177/0004563219830733.

- van Disseldorp C.B., Lambalk J., Kwee J. et al. Comparison of inter-and intra-cycle variability of anti-MЁullerian hormone and antral follicle counts. Human Reproduction. 2010. 25. 221-227. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep366.

- Fong S.L., Visser J.A., Welt C.K. et al. Serum anti-mёullerian hormone levels in healthy females: a nomogram ranging frominfancy to adulthood. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012. 97(12). 4650-4655. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1440.

- Yates A.P., Jopling H.M., Burgoyne N.J. et al. Paediatric reference intervals for plasma anti-Müllerian hormone: comparison of data from the Roche Elecsys assay and the Beckman Coulter Access assay using the same cohort of samples. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2019. 56. 536-547. DOI: 10.1177/0004563219830733.

- Wang J., Yao T., Zhang X. et al. Age-specific reference intervals of serum anti-Müllerian hormone in Chinese girls. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2021. 58(4). 350-357. doi: 10.1177/00045632211002879.

- Broer S.L., Dólleman M., van Disseldorp J. et al. Prediction of an excessive response in in vitro fertilization from patient characteristics and ovarian reserve tests and comparison in subgroups: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Fertil. Steril. 2013. 100. 420-429. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.04.024.

- Moolhuijsen L.M.E., Visser J.A. Anti-Müllerian Hormone and Ovarian Reserve: Update on Assessing Ovarian Function. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020. 105(11). 3361-3373. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa513.

- Silva M.S.B., Giacobini P. New insights into anti-Müllerian hormone role in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and neuroendocrine development. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021. 78(1). 1-16. doi: 10.1007/s00018-020-03576-x.

- Barbotin A.L., Peigné M., Malone S.A., Giacobini P. Emerging Roles of Anti-Müllerian Hormone in Hypothalamic-Pituitary Function. Neuroendocrinology. 2019. 109(3). 218-229. doi: 10.1159/000500689.

- Rudnicka E., Kunicki M., Calik-Ksepka A. et al. Anti-Müllerian Hormone in Pathogenesis, Diagnostic and Treatment of PCOS. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021. 22(22). 12507. doi: 10.3390/ijms222212507.

- Luo E., Zhang J., Song J. et al. Serum Anti-Müllerian Hormone Levels Were Negatively Associated With Body Fat Percentage in PCOS Patients. Front. Endocrinol. 2021. 12. 659717. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.659717.

- Yetim Şahin A., Baş F., Yetim C. et al. Determination of insulin resistance and its relationship with hyperandrogenemia,anti-Müllerian hormone, inhibin A, inhibin B, and insulin-like peptide-3 levels in adolescent girls with polycystic ovary syndrome. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2019. 49(4). 1117-1125. doi: 10.3906/sag-1808-52.

- Merhi Z., Buyuk E., Berger D.S. et al. Leptin suppresses anti‑Mullerian hormone gene expression through the JAK2/STAT3 pathway in luteinized granulosa cells of women undergoing IVF. Hum. Reprod. 2013. 28. 1661-9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/ det072.

- Zeng X., Huang Y., Zhang M. et al. Anti-Müllerian hormone was independently associated with central obesity but not with general obesity in women with PCOS, Endocrine Connections. 2022. 11(1). e210243. https://doi.org/10.1530/EC-21-0243.

- Wiweko B., Indra I., Susanto C. et al. The correlation between serum AMH and HOMA-IR among PCOS phenotypes. BMC Res. Notes. 2018. 11. 114. doi: 0.1186/s13104-018-3207-y.

- Bahadur A., Verma N., Mundhra R. et al. Correlation of Homeostatic Model Assessment-Insulin Resistance, Anti-Mullerian Hormone, and BMI in the Characterization of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Cureus. 2021. 13(6). e16047. doi: 10.7759/cureus.16047.

- Vincentelli C., Maraninchi M., Valéro R. et al. One-year impact of bariatric surgery on serum anti-Mullerian-hormone levels in severely obese women. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2018. 35(7). 1317-1324. doi: 10.1007/s10815-018-1196-3.

- Steegers-Theunissen R.P.M., Wiegel R.E., Jansen P.W., Laven J.S.E., Sinclair K.D. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Brain Disorder Characterized by Eating Problems Originating during Puberty and Adolescence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020. 21(21). 8211. doi: 10.3390/ijms21218211.

- Lian Q., Mao Y., Luo S. et al. Puberty timing associated with obesity and central obesity in chinese han girls. BMC Pediatr. 2019. 19. 1. doi: 10.1186/s12887-018-1376-4.

- Nguyen N.T.K., Fan H.Y., Tsai M.C., Tung T.H., Huynh Q.T.V., Huang S.Y., Chen Y.C. Nutrient intake through childhood and early menarche onset in girls: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2020. 12. 2544. doi: 10.3390/nu12092544.

- Mizgier M., Jarząbek-Bielecka G., Opydo-Szymaczek J., Wendland N., Więckowska B., Kędzia W. Risk factors of overweight and obesity related to diet and disordered eating attitudes in adolescent girls with clinical features of polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2020. 9. 3041. doi: 10.3390/jcm9093041.

- ESHRE/ASRM Rotterdam sponsored pcos consensus workshop group revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 2004. 81. 19-25. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.004.

- Witchel S.F., Roumimper H., Oberfield S. Polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescents. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2016. 45. 329-344. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2016.01.004.

- Geary N. Modulation of appetite by gonadal steroid hormones. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond B Biol. Sci. 2006. 361. 1251-1263. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1860.

- Goodman N.F., Cobin R.H., Futterweit W., Glueck J.S., Legro R.S., Carmina E. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE); American College of Endocrinology (ACE); Androgen Excess and PCOS Society (AES). American association of clinical endocrinologists, american college of endocrinology, and androgen excess and pcos society disease state clinical review: guide to the best practices in the evaluation and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome — part 1. Endocr. Pract. 2015. 21(11).

- Moran L.J., Grieger J.A., Mishra G.D., Teede H.J. The association of a mediterranean-style diet pattern with polycystic ovary syndrome status in a community cohort study. Nutrients. 2015. 7. 8553-8564. doi: 10.3390/nu7105419.

- Cimino I., Casoni F., Liu X. et al. Novel role for anti-müllerian hormone in the regulation of gnrh neuron excitability and hormone secretion. Nat. Commun. 2016. 7. 10055. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10055.

- Malone S.A., Papadakis G.E., Messina A. et al. Defective AMH signaling disrupts gnrh neuron development and function and contributes to hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. eLife. 2019. 8. e47198. doi: 10.7554/eLife.47198.

- Piltonen T.T., Giacobini P., Edvinsson A. et al. Circulating antimüllerian hormone and steroid hormone levels remain high in pregnant women etwith polycystic ovary syndrome at term. Fertil. Steril. 2019. 111. 588-596. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.11.028.

- Basile S., Noti G., Salvati L., Artini P.G., Mangiavillano B., Pinelli S. Factors leading to primary ovarian insufficiency: a literature overview. Gynecological and Reproductive Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2021. 2(2). 85-92.

- Alkhzouz C., Bucerzan S., Miclaus M., Mirea A.M., Miclea D. 46,XX DSD: Developmental, Clinical and Genetic Aspects. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021. 11(8). 1379. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11081379.

- Weintraub A., Eldar-Geva T. Anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) determinations in the pediatric and adolescent endocrine practice. Pediatr. Endocrinol Rev. 2017. 14. 364-370. doi: 10.17458/per.vol14.2017.WG.Mullerian.

- Miller W.L. Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia: Time to Replace 17OHP with 21-Deoxycortisol. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2019. 91. 416-420. doi: 10.1159/000501396.

- Cools M., Nordenström A., Robeva R. et al. Caring for individuals with a difference of sex development (DSD): A Consensus Statement. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018. 14. 415-429. doi: 10.1038/s41574-018-0010-8.

- Peek R., Schleedoorn M., Smeets D. et al. Ovarian follicles of young patients with Turner’s syndrome contain normal oocytes but monosomic 45,X granulosa cells. Hum. Reprod. 2019. 34(9). 1686-1696.

- von Wolff M., Roumet M., Stute P., Liebenthron J. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) concentration has limited prognostic value for density of primordial and primary follicles, questioning it as an accurate parameter for the ovarian reserve. Maturitas. 2020. 134. 34-40. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.02.001.

- van der Kooi A.L., van den Heuvel-Eibrink M.M., van Noortwijk A. et al. Longitudinal follow-up in female childhood cancer survivors: no signs of accelerated ovarian function loss. Hum. Reprod. 2017. 32(1). 193-200. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew278.

- Gupta A.A., Lee Chong A., Deveault C. et al. Anti-Müllerian hormone in female adolescent cancer patients before, during, and after completion of therapy: a pilot feasibility study. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2016. 29(6). 599-603. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2016.04.009.

- Grinspon R.P., Gottlieb S., Bedecarrás P., Rey R.A. Anti-Müllerian hormone and testicular function in prepubertal boys with cryptorchidism. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2018. 9. 182. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00182.

- Misra M., MacLaughlin D.T., Donahoe P.K., Lee M.M. Measurement of Mullerian inhibiting substance facilitates management of boys with microphallus and cryptorchidism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002. 87(8). 3598-3602.

- Hamdi S.M., Almont T., Galinier P., Mieusset R., Thonneau P. Altered secretion of Sertoli cells hormones in 2-year-old prepubertal cryptorchid boys: a cross-sectional study. Andrology. 2017. 5(4). 783-789. doi: 10.1111/andr.12373.

- Cortes D., Clasen-Linded E., Hutsonefg J.M., Li R., Thorup J. The Sertoli cell hormones inhibin-B and anti Müllerian hormone have different patterns of secretion in prepubertal cryptorchid boys. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2016. 51(3). 475-480. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.08.059.

- Edelsztein N.Y., Grinspon R.P., Schteingart H.F. et al. Anti-Müllerian hormone as a marker of steroid and gonadotropin action in the testis of children and adolescents with disorders of the gonadal axis. Int. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2016. 20. (2016). doi: 10.1186/s13633-016-0038-2.

- Rey R.A. Recent advancement in the treatment of boys and adolescents with hypogonadism. Therapeutic Advances in Endocrinology and Metabolism. First Published January 5, 2022. doi: 10.1177/20420188211065660.

- Raygorodskaya N.Y., Bolotova N.V., Chekhonatskaya M.L., Polyakov V.K., Sedova L.N., Somova V.A. Diagnosis of congenital sexual maldevelopment in boys with bilateral inguinal cryptorchidism during minipuberty. Probl. Endokrinol. (Mosk.). 2019 Dec 25. 65(4). 236-242. Russian. doi: 10.14341/probl9854.

- Zhao H., Lv Y., Li L., Chen Z.J. Genetic studies on polycystic ovary syndrome. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016. 37. 56-65. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2016.04.002.

- Caanen M.R., Peters H.E., van de Ven P.M. et al. Anti-Müllerian Hormone Levels in Adolescence in Relation to Long-term Follow-up for Presence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021. 106(3). e1084-e1095. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa949.

- Gorsic L.K., Kosova G., Werstein B. et al. Pathogenic Anti-Müllerian Hormone Variants in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017. 102(8). 2862-2872. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-00612.

- Weintraub A., Eldar-Geva T. Anti-Mullerian Hormone (AMH) Determinations in the Pediatric and Adolescent Endocrine Practice. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Rev. 2017. 14(4). 364-370. doi: 10.17458/per.vol14.2017.WG.Mullerian.

- Xu H., Zhang M., Zhang H., Alpadi K., Wang L., Li R., Qiao J. Clinical Applications of Serum Anti-Müllerian Hormone Measurements in Both Males and Females: An Update. Innovation (NY). 2021. 9. 2(1). 100091. doi: 10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100091.

- Kanakatti Shankar R., Dowlut-McElroy T., Dauber A., Gomez-Lobo V. Clinical Utility of Anti-Mullerian Hormone in Pediatrics. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022. 107(2). 309-323. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab687.

- Lucas-Herald A.K., Kyriakou A., Alimussina M. et al. Serum Anti-Müllerian Hormone in the Prediction of Response to hCG Stimulation in Children With DSD. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020. 105(5). 1608-1616. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa052.

- Lv P.P., Jin M., Rao J.P. et al. Role of anti-Müllerian hormone and testosterone in follicular growth: a cross-sectional study. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2020. 20(1). 101. Published 2020 Jul 8. doi: 10.1186/s12902-020-00569-6.

- Moolhuijsen L.M.E., Visser J.A. Anti-Müllerian Hormone and Ovarian Reserve: Update on Assessing Ovarian Function. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020. 105(11). 3361-3373. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa513.

- Fu Y.X., Wang H., Hu T., Wang F.M., Hu R. Factors affec–ting the accuracy and reliability of the measurement of anti-Müllerian hormone concentration in the clinic. J. Int. Med. Res. 2021. 49(5). 3000605211016161. doi: 10.1177/03000605211016161.

- Tadaion Far F., Jahanian Sadatmahalleh S., Ziaei S., Kazemnejad A. Comparison of the umbilical cord Blood's anti-Mullerian hormone level in the newborns of mothers with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and healthy mothers. J. Ovarian. Res. 2019. 12(1). 111. doi: 10.1186/s13048-019-0583-4.

/38.jpg)

/41.jpg)